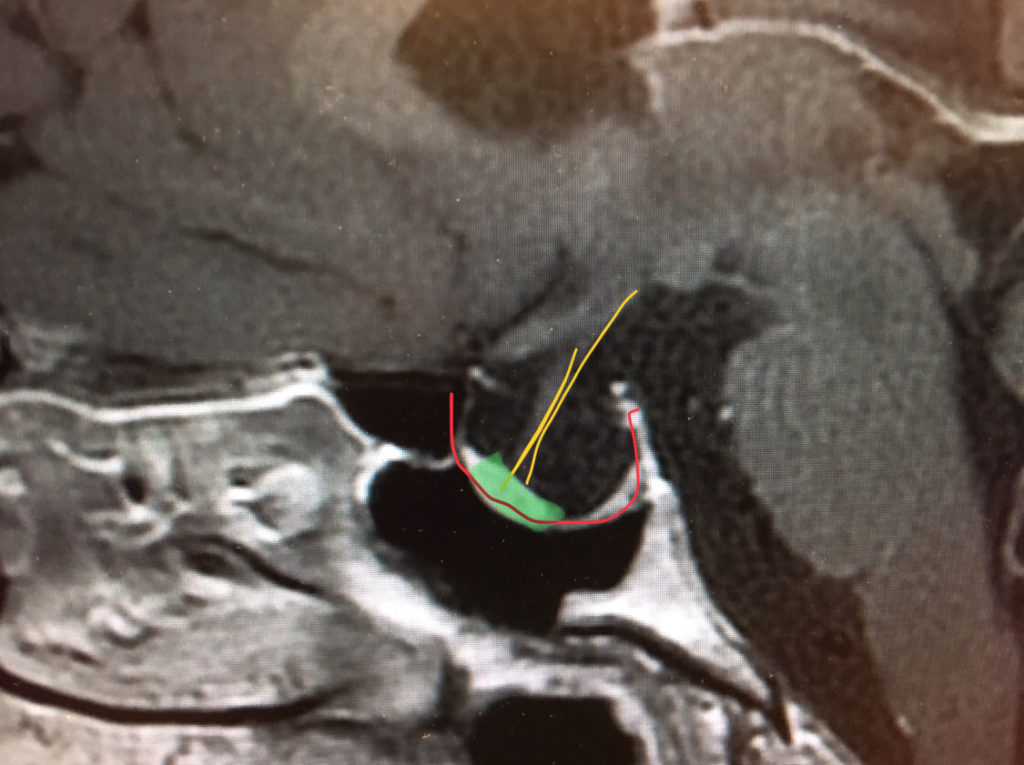

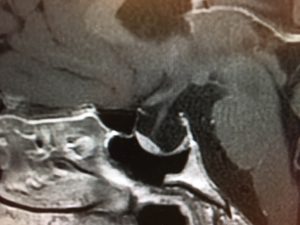

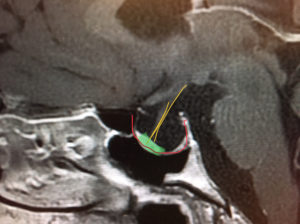

From Lewis S. Blevins Jr. M.D. – Pituitary World News co-founder and Director of the Center for Pituitary Disorders at UCSF. – I had the pleasure of seeing a very interesting patient recently who was referred for evaluation of an empty sella and hyperprolactinemia of a modest degree. Her menstrual history was consistent with possible hyperprolactinemia dating 20 to 30 years prior to our visit. Recent prolactin terminations were modestly elevated in the 50 to 60 picogram per milliliter range. MRI demonstrated an empty sella with a thinned and stretched infundibulum and a small pituitary gland in the lower front part of the sella. Furthermore, the sella turcica was rather much enlarged and, as far as volume is concerned, about four times the size of the usual sella.

My assessment was that she had a secondary empty sella likely due to a prior prolactinoma that had degenerated or infarcted and resorbed over time. This assumption is based on the fact that she had hyperprolactinemia, a history compatible with having had a long-standing pituitary adenoma, and a very enlarged sella. More information on empty sella syndrome in this aticle by Dr. Blevins

It is conceivable that she has microscopic tumor cells secreting prolactin accounting for the modest hyperprolactinemia as there was no other identifiable cause of hyperprolactinemia in this patient. This particular situation has been described in patients with prolactinomas. It has also been described in patients who present with features of acromegaly and very similar radiographic findings but no biochemical evidence of active disease. I have also seen it in at least one patient with a history compatible with Cushing’s disease due to a presumed macroadenoma of the gland that had degenerated at some point in time resulting in resolution of cushingoid features. Empty sella syndrome may be the end result of some cases of pituitary apoplexy rather than necrosis. It may also result after successful surgical removal of a large pituitary adenoma.

Other causes of secondary empty sella include lymphocytic hypophysitis and other inflammatory disorders that destroy the pituitary gland, Sheehan syndrome, sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, sickle cell disease, midline granuloma, Wegener granulomatosis, head trauma with transection of the pituitary infundibulum, etc. The pituitary function may be normal or abnormal depending on the underlying process leading to the empty sella.

Primary empty sella, on the other hand, is a congenital disorder of varying severity that is present in about 2% of patients who undergo MRI imaging of the brain. In my experience, growth hormone deficiency is the most common, and often times the only, abnormality of pituitary function in these patients.

All patients with empty sella deserve an investigation of anterior pituitary functions, hormone replacement if necessary, and consideration as to the potential underlying cause of the disorder so that all implications and consequences of such can be addressed.

© 2018 – 2022, Pituitary World News. All rights reserved.